Addiction is not a choice. It is a treatable medical condition.

Stigma prevents people from getting the help they need.

Explore real stories

Substance use is often hidden – people suffer from stigma in silence

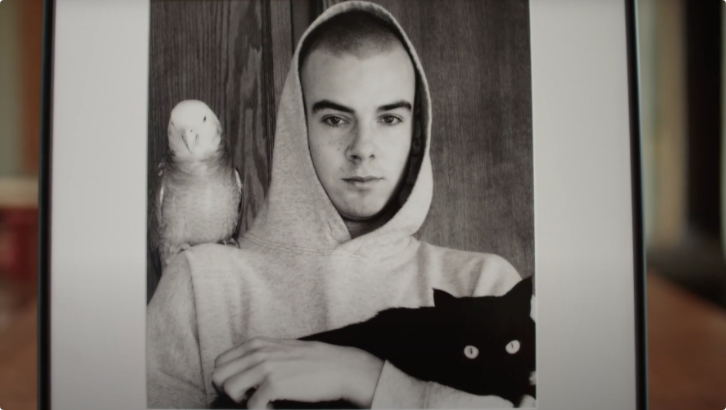

In this heart-wrenching talk, Petra shares Danny’s story and the idea that people who use drugs are just like everyone else: people who deserve a chance to be safe and healthy, and to live without judgment or shame.

Substance use is often hidden – people suffer from stigma in silence

In this heart-wrenching talk, Petra shares Danny’s story and the idea that people who use drugs are just like everyone else: people who deserve a chance to be safe and healthy, and to live without judgment or shame.

Your empathy and compassion can help save a life

What if shame and stigma could be eliminated? What if you could replace them with empathy and compassion? How many lives could you save? Sarah Keast, a widow, writer and activist explores these questions as she shares her powerful story of love and loss.

Your empathy and compassion can help save a life

What if shame and stigma could be eliminated? What if you could replace them with empathy and compassion? How many lives could you save? Sarah Keast, a widow, writer and activist explores these questions as she shares her powerful story of love and loss.

Because of stigma, I was denied help

Tina speaks about the stigma she has experienced as someone living with substance use disorder.

Because of stigma, I was denied help

Tina speaks about the stigma she has experienced as someone living with substance use disorder.

Sharing his story helps me heal – if it saves one kid, it’s worth it

Listen to Jordan's story and how his dependence on pain medication led to tragedy.

Sharing his story helps me heal – if it saves one kid, it’s worth it

Listen to Jordan's story and how his dependence on pain medication led to tragedy.

Counseling has helped me in many ways

Listen to Karlee's story about her prescription drug use, its negative effects on her life and how she recovered.

Counseling has helped me in many ways

Listen to Karlee's story about her prescription drug use, its negative effects on her life and how she recovered.

I was always ashamed to tell my story, but now I want to help others because I was helped

Hear Meagan's story about how her prescription drug use quickly turned into high-risk substance use. Also find out how she got treatment.

I was always ashamed to tell my story, but now I want to help others because I was helped

Hear Meagan's story about how her prescription drug use quickly turned into high-risk substance use. Also find out how she got treatment.

She was a typical little girl. Very popular.

Meagan’s mother:

She loved kids, loved babysitting. We had a wonderful relationship.

Meagan’s father:

Don’t take it for granted that they seem happy in front of you, that it can’t happen to them. It can happen to any person’s child.

Meagan:

I can’t say why I did it, but I was just fed up and mad. It made me feel tough. Once I started using opiates, I changed into a completely different person. I didn’t care about anybody. I would steal. I would lie.

Meagan’s mother:

And it didn’t take long. I’m not talking weeks, it was just days.

Meagan’s father:

Yeah.

Meagan’s mother:

And my daughter was hooked.

Meagan:

I would wake up in the morning and my legs would be throbbing. You’re throwing up. You’re freezing all the time. It’s excruciating. And it got me so bad. It got me so bad. I didn’t know that. I didn’t think I was going to be able to get out of it.

Meagan’s father:

You have your child just disintegrating in front of you.

Meagan’s mother:

Not even my friends and family understood. Nobody understands. Nobody gets it.

Meagan:

It feels like I woke up one morning and I just said, “This is enough. If I want to do drugs, I’m going to lose my baby girl.” I went to my parents and I had told them that I needed help. And that’s when we started seeking information about the treatment center. I met a counsellor and she changed my whole life.

Meagan’s father:

Totally rejuvenated to a person that we were able to talk to. To see her cooking a meal, it was just amazing to us to see her doing that.

Meagan:

I have now been clean for almost a year and a half. I’m trying to get my grade 12 right now.

Meagan’s father:

Meagan has always had the desire to get married, settle down. I hope that I’m able to walk down that aisle.

Meagan:

And I used to be ashamed of telling people my story. And now, I just want to help people because I’ve been helped. I am feeling what it’s like to be normal again.

Narrator:

Get the facts and talk with your kids about prescription drug abuse. Visit canada.ca/drugprevention. A message from the government of Canada.

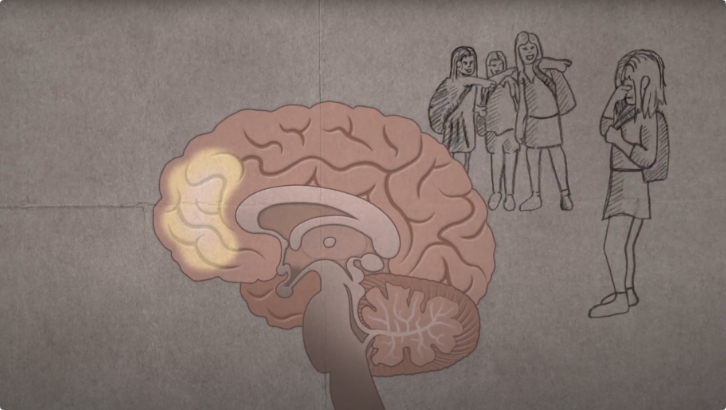

Addiction is not a choice – trauma and addiction changes your brain

How trauma impacts the brain: reducing stigma around addiction and substance use.

Addiction is not a choice – trauma and addiction changes your brain

How trauma impacts the brain: reducing stigma around addiction and substance use.

See the person, not the addiction

Listen to the stories of 12 people with firsthand or family experiences of drug use. Through these stories, we hope to build compassion, encourage empathy, and contribute to a community that treats all people with dignity and respect.

See the person, not the addiction

Listen to the stories of 12 people with firsthand or family experiences of drug use. Through these stories, we hope to build compassion, encourage empathy, and contribute to a community that treats all people with dignity and respect.

Addiction’s a really hard thing. I know there’s really – there’s conflict, right? People think that it’s a choice, whereas I think it’s more of a disease. It’s a fight for that person.

[music]

Intertitle

Stop Stigma. Save Lives. The impact of empathy.

Sheldon:

To walk a mile in an addict’s shoes would go a long way. And not so much as to walk in their shoes, but, you know, to be beside them or to know what they’re going through, and why they’re at that point in their life.

Jolene:

When people judge me for being a working girl, it hurts. They just take one look at me and I know exactly, you know, the reaction they get on their face is like: “Oh, gross” or “Oh, ew, look at her …she’s an addict,” or “she sells her body.” It hurts a lot, you know. I’m a good person. If they really got to know me, they’d really like me.

[music]

Intertitle

Stigma against people with addictions can sometimes do more damage than the addiction itself.

Jolene:

The way I’d like to be treated is with respect and dignity, and like a human being—like everybody else gets treated. Instead of, like, just looking at me and judging me for my addiction and my appearance, you know, and for being native.

Jeremy:

To be known as Jeremy, not “Jeremy the drug addict” or “Jeremy the thief” or whatever.

[music]

Intertitle

Simply treating people with respect and changing our language can help save lives.

Charlene:

When you see injustices, when you see things that aren’t right, when you see that people are being treated poorly. If you can make a change for the better for anybody, I think we owe that to our community members.

[music]

Intertitle

Stop Stigma. Save Lives. Learn more: northernhealth.ca/stigma

Jolene:

We’re all made to love and care for people. Why can’t we show everyone – everyone – that love and care?

Elsa’s Story

Elsa is a social worker at a harm reduction organization. Every day she offers support and compassion to people with substance use disorders. Let’s listen to her story!

Elsa’s Story

Elsa is a social worker at a harm reduction organization. Every day she offers support and compassion to people with substance use disorders. Let’s listen to her story!

Narrator:

In Plain Sight is a Health Canada audio series that explores the personal stories of people affected by the opioid crisis.

The most recent data shows that every day, approximately 12 people die from opioid overdoses in Canada.

We see this on the news. We know that it’s happening. We know that it’s real. Yet, we tell ourselves that it couldn’t happen to the people we know, the people we work with, the people we love. That it couldn’t happen to us.

The reality is, the opioid crisis is happening right before our eyes, in plain sight, and it can affect anyone. There are thousands of stories waiting to be heard.

Elsa is a social worker at a harm reduction organization. Every day she offers support and compassion to people with substance use disorders. Let’s listen to her story…

Elsa:

My name is Elsa. I’m a social worker. Basically, what I do is work directly with people according to their needs, but always in terms of their substance use. We can offer to set up a meeting with a social worker to help them achieve their goals, no matter what those are – reducing their substance use, quitting, asking questions, getting information, or asking questions about a family member who’s using. We also provide all the sterile equipment such as crack pipe kits, injection kits, naloxone kits, and always with information and education. But we also go out into the community of substance users. We meet them in their environment, always with the aim of improving their living conditions and meeting their needs in terms of the distribution and equipment they need. The person is truly at the heart of our interventions and our mission; our priority is always the well-being of the person being helped.

My biggest challenge is to get people who want to get involved, but who have all too often been excluded and judged, to see their experience really as something positive, something they can pass on to someone else. So that it becomes an experience that helps them and others as well. Basically, my work allows me to encourage those same people to deliver their message, claim their rights, name the injustices they have suffered. It’s always a matter of giving those people back their power over their lives, their rights, their voices, and that’s a challenge in itself, because when people feel socially excluded, it’s not easy to get them to consider their experience as a form of expertise that can help others. To come to that awareness is one thing; and then there’s connecting with other people who are using, not necessarily the same substance, not necessarily the same experience, not the same age – that’s another challenge. You know, there are clashes in the kinds of drug use, the kinds of substances, even the way they’re administered. Someone who injects, someone who smokes, it’s very different, even though there are a lot of similarities, but for the people who are living that life, it’s hard, you know, to create a bond of trust with someone who isn’t like them or isn’t using the same drugs or isn’t the same age.

I think that through my role, really, I encourage them to consider their experience as meaningful, you know. And that allows them to see another side of the story, because for some people, it’s the first time in their lives they’ve been told it’s something positive, you know, a kind of expertise. Whereas they’ve always thought of it as the most difficult period of their lives, a time that taught them nothing. You know, they’ve often experienced a lot of judgment and rejection from their own family, you know, from their job. They’re homeless, they’re in a really tough situation, and then they realize for the first time that they have rights. There are a lot of users, you know, there are a lot of people who want to claim these same rights. So that makes community solidarity a challenge, but it’s not impossible. I see now – and it took me awhile – that it’s something that builds up gradually, but now there’s a good solidarity and a respect for the experience of others, no matter where they come from, and when someone even more marginalized than they are joins the group, they get an unconditional welcome. So it’s even more beautiful, you know. It’s a worthy challenge, I think, that it’s a long-term thing, something to be achieved in the long run, it takes patience. You know, solidarity within a group doesn’t happen in a single meeting. They come because they know it’s an opportunity to get together with other people with lived experience, but they don’t necessarily know where it’s headed.

In order to help people who use drugs, you have to adapt a range of services for a range of people. The same goes for access to substitution therapy, now called opioid antagonist therapy: people aren’t offered many choices, if they’ve tried methadone and it didn’t work, if they’ve tried Suboxone and that didn’t work either, what can we offer? What can we offer a person who’s decided to take a safer approach to their substance use, who’s seeking treatment as a positive alternative for their survival and their health, and who voluntarily puts aside the risks of using a contaminated substance, but who finds themselves with no other choice than to repeat a treatment that doesn’t meet their needs? Treatment restrictions can have far more dangerous consequences, especially with respect to the unsafe supply of substances. Although doctors can prescribe medical heroin, which could be considered access to a safe supply, very few do. Because, let’s face it, these days, when you get your drugs in the traditional way you’re not talking about a safe supply. You’re at high risk of using a contaminated substance. Not to mention the conditions, not forgetting the conditions related to substitution therapy, the whole model of reward and punishment, it really doesn’t meet the needs of the person who is using. In fact, the person has to go to the pharmacy every day for safety and supervision purposes. The pharmacist will make sure that the person actually takes their medication properly, so there’s really a mouth check. The person has to take urine tests. At any point, have we taken the time simply to ask the person what they need? If the person’s urine test comes back positive, ultimately they can be cut off from treatment and lose the so-called privilege of getting a prescription for two or three days’ worth of medication so they don’t have to go to the pharmacy every day. We talk about patient safety. I see the opposite, because when you deprive someone of the treatment that person wants—and you have to understand that when they go for treatment, they may already be having withdrawal symptoms. So they’ll wait until morning to go for treatment, but what about a person who’s experiencing withdrawal symptoms and who’s been cut off from treatment—well, where are they going to go to get supplies? In terms of safety, there’s nothing less safe than that. It pretty much guarantees that they’ll go get a fix in their familiar environment instead of seeking treatment. There are people who use while they’re in treatment – it’s a fact. I think we have to start from there. Because if we don’t focus on what the person needs, well, we’re jeopardizing their safety.

People undergoing treatment often face judgment even when they go to the pharmacy. Some pharmacies require people on methadone or Suboxone therapy to go through to the back. That’s quite something for them, being made to feel different. And I ask myself, how do we explain that people who have a prescription for morphine are free to buy their pills in considerable quantities and take them home without ever having to take a urine test, and without necessarily having complete information about what is prescribed? There’s a real split between the two, and don’t think the people going for treatment don’t see that. You know, they feel like they’re being monitored, and it’s hard for them, feeling the judgment of the pharmacist every time they show up to pick it up. And asking someone to pick up a prescription every day, that doesn’t take the person’s experience into account. When you’re living in chaos, it’s not easy to stick to a routine. You know, it takes a long time to get there in the morning, and then you have to wait. Getting there in the morning doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be the first one seen, and it happens, you know… people have told me they wait much longer than others for their treatment. For me, that’s really a big gap, because I think we should offer the person diversity, choice, and support when it comes to treatment, there are people who get put on the treatment without necessarily knowing what it really is, without being warned that they’ll experience withdrawal symptoms every time their dose is reduced. There’s a real need for support and information for people who want treatment. There is also the fact that, well, we can prescribe medical heroin, but very few doctors do it. So that’s not an option either. I know there are studies on injectable treatments, but we’re not there yet. You know, it’s harder, but when you consider that people are using unsafe substances and dying as a result, it’s important to think seriously about changing that, because we’re talking about people who are motivated to seek treatment. These are people who have already come to that point. We’re not talking about people who aren’t interested in treatment. They are at that point, they want it, but they don’t have the information, they don’t know how it works. They feel unsupported, they feel judged at the pharmacy. As far as I’m concerned, this is a big problem.

The stigma attached to substance use, and by extension to substance users, is probably the biggest barrier in our work. Yet we all know that substance use is everywhere, you have to forget the image of the person injecting themselves in an alley between two dumpsters. Stigmatization, people who use face it every day, and even those who quietly leave that environment still experience it. It’s very discouraging, you know, to make some progress, to stop using, and still feel you’re being judged by people—family or even, you know, the police, the hospitals. There’s a sort of loss of hope in the person… It’s difficult when you make the journey, and you end up, you know, recognizing that “I did it,” yet you feel that people still look at you the same way, that you’re still perceived as someone who uses drugs and who is problematic. That’s just about enough to make a person want to give up. Fortunately, I’ve seen many who didn’t go down that road, but decided instead to defend their rights, but you have to realize that a person who’s stopped using and is on the road to recovery is not necessarily the strongest person in the world. It’s still a fragile time for the person, and the way people look at them carries a lot of weight. Stigmatization, you know, we’ve seen it, is being stopped and searched as you cross the street, while other people cross the street and don’t get stopped. It’s also going to the hospital with an injection-related abscess and being treated by the staff as if you were contagious, and dangerous. It’s going to the pharmacy and having to go through to the back; it’s being told “you just have to stop, it’s a matter of willpower;” it’s being labelled a troublemaker. Sure, using when you’re homeless is a lot more visible, but do we really try to put ourselves in that person’s shoes when we find it personally upsetting?

People who are using face discrimination on a daily basis because of their social status, and from different sides, like the justice system, the health care system, the welfare system, their family, their friends… and it can even be at the grocery store, it’s literally everywhere.

When you’re in the business of advocacy, you know you’re not always going to be in public favour. We’re dealing with several issues. We’re talking about solutions, and they’re not necessarily the solutions that the average person would come up with. That’s the most difficult part, I would say. The current system is prohibitionist, and by criminalizing drug use it has created a judgmental atmosphere that infantilizes and stigmatizes people who use drugs, because they are perceived as a burden or a threat. I think we really need to change our perspective, both individually and collectively, and educate ourselves not only about drugs per se, but also about the harm reduction approach, which we don’t often see but which has shown the most significant results in terms of health promotion and implementation of safer practices for overdose prevention. Right now we’re in the middle of a public health crisis; people are dying, it’s literally a matter of life and death. Behind the overdose statistics that we see… it’s not just numbers, you know, it’s people, and, especially, it’s mothers, fathers, aunts, grandfathers, friends, colleagues, people who may have been closer to you than you think. The most important message, I think, is that no one is safe. We all have someone close to us who’s using, whether we know it or not, but it’s not necessarily problematic for everyone. I think that regardless of whether or not you’re using, you really need to be informed, because it can happen to you too…

I never thought this job would be easy, but let me tell you, when I get home safe and sound I sometimes think about the people who can’t even count on the word “safety.” Those people are in survival mode. I understand the survival instinct, and that allows me to better understand their reality. When you have nothing, what do you do? When we try to put ourselves in their position, the social workers, even we sometimes say to ourselves that we couldn’t do it, but seeing the positive impact we can have on their lives, even when they have absolutely nothing, as far as I’m concerned, that’s my paycheque.

When it affects you personally, especially in a job like this, it’s hard to,you know, you have a unique relationship with the person. You’re not their mother, you’re not their friend, you’re not a co-worker; you’re the person who helped them with their substance abuse. When this person dies because of their substance abuse, you wonder what you could have done to change that, you know. But the reality is that there was nothing to be done. All we can really do is be there. But sometimes those deep wounds can’t be healed. I’m not a doctor, I’m not a psychologist, and sometimes, despite all the professional help they may have access to, a person’s unhappiness can be really deep and difficult to reach and heal.

I think that as a social worker, you have to be constantly aware of the emotional work you’re doing. When we’re working with people, we always put up a barrier; we don’t take on their emotions, you know, we’re there to put ourselves in the other person’s place, to understand and support them. Because if we take on their emotions, we’re not helping them. If the person is crying and I start crying, that won’t do any good. But the emotional work, sometimes you’re not aware of the magnitude of it until you get home and realize that you experienced, you know, something that … People come to see us every day and tell us about the darkest moments of their lives. We never let them go, there’s always something going on. So it’s really important to consciously get some distance when you get home. I think, you know, there are some social workers who’ve lost the ability to keep that separate. I haven’t been doing this for 20 years. So I’m still working on that, but it’s really important, because emotional fatigue can set in. You see it a lot among community workers. It happens pretty regularly: the social workers take some time off, then they come back to work. It’s important to look after our mental health. And I think it’s also important to be well supported by your organization. In my organization we don’t talk about sick leave, we talk about wellness leave. It’s a simple distinction, but it changes the way we look at things. We’re encouraged to take time off when we don’t feel right, not just when we have a sore arm or a headache. Because in our line of work it’s important to really be present and ready to listen to the person, regardless of how you yourself are doing and how you might be feeling on any particular day. It’s important. And I think the priority is to ask yourself, “Am I ready to go to work today and to listen to people? Or am I upset about something, or do I feel like I didn’t get a wink of sleep all night and might not be the best advocate for the person?” It’s a job in itself to consider and recognize those limits. It’s something I’ll probably be working on all my life. But that’s part of the job. That said, I do it mostly because I’m intrinsically motivated. For me, it’s a passion. So for sure there are emotions involved. So I have to try to figure out what the emotion is and what to do with it, you know. I find that doing advocacy work is a great way to deal with emotions: to focus on the solution, not the problem … to keep moving forward. It’s fun for me, you know, to keep moving forward and finding solutions, but it’s also nice for people who are beset by problems to believe that yes, there is a solution. And there are rights to be defended, claims to be made. You know, you have the right to be defended because you are a person like any other. That’s what really helps me to channel my emotions, to kind of transform them into motivation, which helps me to advocate on behalf of people who are using.

Narrator:

Tragically, the number of opioid-related deaths in Canada continues to increase each year. This crisis is affecting the health and lives of people from all walks of life, all age groups and all social and economic backgrounds. Elsa shares her thoughts on what could be done to help reduce the number of opioid-related overdoses and save lives.

Elsa:

I believe we have to hope for change at both the structural and the legislative level, as well as a change in our level of investment in the repressive and prohibitive model, which has shown that none of the measures implemented so far seem to reduce mortality rates consistently. At the moment, the legislative framework for substance use doesn’t allow us to save lives, and more important, it criminalizes a whole community of people. Remember, people who use illegal drugs are still considered criminals in Canada. But are they really criminals? If we label them criminals and put them in jail, are we really promoting their health, are we really helping them? They are people just like you, and if one day you find yourself in a precarious situation and you start using, whether or not that becomes problematic, I’m convinced that you wouldn’t want to be seen as a criminal. I believe we have to act, and not lose sight of the source of the problem. Beyond criminalization, there’s a real problem with the supply of substances.

Currently, the supply of contaminated drugs, which aren’t subject to any form of quality control, is a determining factor in overdose deaths, and it’s also what allows users to keep using. Why is drug contamination dangerous? Because we think the risk has to do with street drugs, street users, but we know that people who use drugs don’t all come from that background, and if they don’t, they may not be aware of the resources. Basically they could end up, for instance, in a situation where one weekend they decide to use cocaine recreationally (which happens, we all know it), without even considering that it might be contaminated, without knowing that there are organizations distributing test kits to detect the presence of fentanyl. So they’re at risk of overdose, and they may not have the information they need to avoid this kind of situation. If I ask you this: If you use twice a year, have you thought about having your naloxone kit with you? The supply of contaminated drugs and the criminalization of this drug use put you at risk of overdose and label you as a criminal. We need change, and fast, because the number deaths is now in the thousands.

I had the immense privilege of working with someone whose journey amazes me to this day. I watched them grow and recognize their strengths, through all the opportunities for involvement they had. The truth is that this person taught me a lot about myself. Considering the sheer weight of their experience, the tears they shed when they shared their story with me, it’s impressive to see how adaptable human beings can be in survival mode, and how, too, they can recover. Today, this person draws on their experience, their expertise, to advocate for people who have travelled a similar path. I think the important thing here is that there’s hope in every story… you just have to find the positive in the details, because if we don’t believe it ourselves, we can’t help the person achieve self-worth and self-trust. It was probably through that person that I learned the most.

Narrator:

Problematic opioid use is devastating Canadian lives. The numbers are tragic and staggering. These are the stories behind the numbers. This crisis has a face. It is the face of a friend; a co-worker; a family member. Meeting those eyes, and seeing our own reflection is the first step toward ending the stigma that often prevents people who use drugs from receiving help. To learn more about the opioid crisis, visit Canada.ca/Opioids.

This audio series is a production of Health Canada. The opinions expressed and language used by individuals on this program are those of the individuals and not those of Health Canada. Health Canada has not validated the accuracy of any statements made by the individuals on this program. Reproduction of this material, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes is permitted under the standard Terms of Use for Government of Canada digital content.

Melissa's Story

The reality is, the opioid crisis is happening right before our eyes, in plain sight, and it can affect anyone. There are thousands of stories waiting to be heard. This is where Mélissa’s story begins…

Melissa's Story

The reality is, the opioid crisis is happening right before our eyes, in plain sight, and it can affect anyone. There are thousands of stories waiting to be heard. This is where Mélissa’s story begins…

In Plain Sight is a Health Canada audio series that explores the personal stories of people affected by the opioid crisis.

Every day, approximately 11 people die from opioid overdoses in Canada.

We see this on the news. We know that it’s happening. We know that it’s real. Yet, we tell ourselves that it couldn’t happen to the people we know, the people we work with, the people we love, that it couldn’t happen to us.

The reality is, the opioid crisis is happening right before our eyes, in plain sight, and it can affect anyone. There are thousands of stories waiting to be heard.

This is where Mélissa’s story begins…

Mélissa:

I had a good job as a client care attendant for people, uh … who had terminal bone cancer. I had a great condo, a nice new car, a sports car, Tiburon, manual. My family didn’t think I’d get it, but I got it. It was a point of pride for me. I had lots of good friends, and I used coke occasionally. And my family relationships were going really well.

When I was 14, in high school, I hung out with some guys from Ottawa, and we did speed. When I was 18 I met a guy, a serious relationship that lasted 7 years. We broke up because of cheating, and then I started to work as an escort because it paid well. I started putting ads in the newspaper. I did some porn, and that led me to organized crime. I felt safe with them: if ever anything happened to me, I just had to call them and they’d take care of it.

That’s when one of them moved in with me. I wanted to help him out—little did I know what that would involve. After he OD’d, I saved his life. And by way of thanking me, he paid my rent and introduced me to heroin, which he bought for me. I was 24 years old at that time.

I realized things weren’t right when I was 28. I was doing heroin, crack, speed, oxys and fentanyl. It all fell apart when I lost everything: my boyfriend, my apartment, my friends, my furniture, my clothes and my personal hygiene. I was ashamed of myself. It got to the point where I was squatting in abandoned houses with no heat and no running water. I owed money to the drug dealers and the government.

I defrauded the banks by putting empty envelopes in the ATMs. I had about 20 different credit cards, with limits from $100 to $5,000. I lost my driver’s licence. I now have a criminal record, and as everyone knows, when you have a criminal record you’re stuck with minimum wage jobs for the rest of your life. My car was repossessed by the company because I couldn’t make the payments anymore. I was 28 years old, I went bankrupt, and I was on probation for the next three years.

So here I was at 28, on the street, no housing, tons of debt, no car, tons of family problems. I didn’t know what to do. My instinct went into survival mode. Rule number 1 was using. Every hour, every minute, and every second of the day, I had to get my fix. I’d stay with one person, then another for a few days at a time. Sometimes I had no place to sleep, so I’d sleep on a park bench, in any old park.

I had no hygiene, and I weighed 80 pounds. I’m 5’ 6”, so technically I should weigh 125 pounds. I was literally skin and bones. When I had no money for drugs, I turned to prostitution, or easier yet, I slept with the dealers in exchange for drugs.

Using is truly a demon that thinks for you, acts for you, and controls you in an incredibly cruel way. It literally tears you apart. I used with several people. And people will steal from you, they’ll manipulate you to get your stash. When you live on the street, your life is in constant danger. I got into even more trouble with the law—another probation, for one thing—and had even more family problems.

I lived on the street for three years. After three years, I was literally exhausted, both physically and mentally. In January 2018, I started therapy for the first time in my life at the CRDO [Centre de réadaptation en dépendance de l’Outaouais]. I stayed for two weeks, because I thought I’d be cured when I finished therapy. Therapy is really hard when you’re using. You’re scared, you don’t know what to expect. It’s change, and sometimes you’re not ready to change.

I had relapse after relapse—you always return to your old patterns of consumption. In May 2018, I went back into therapy and successfully completed a 38-day program. You’re safe in therapy. I succeeded and I’m proud of it. You learn a lot of things in therapy, but the most important thing when you come out is how people react when they see you: you’re healthy, you’ve gained weight, you don’t have dark circles under your eyes, it’s all wonderful. I’m fine now, but I relapsed on the 75th day. Why? Because I fell back into my old patterns of consumption.

What I’ve learned about myself is that I’m beautiful, that I can be happy without drugs. I have to think of myself before others. It’s important to talk to someone when things start to go wrong. I got my independence back. Now, at 32, I have my own apartment, I cook for myself, I’m important, and it’s true that sleeping on something often brings a solution. I weigh 115 pounds. I haven’t used in 2 months and 2 days. It’s hard work, but it’s worth it. Being happy and not using is the best gift I could have given myself.

Another thing I learned is that when I was using, I had lots of friends, and now my old friends think I’m boring—and that’s normal, I’m not using anymore. I’ve built a new circle of friends, I have confidence in myself and that’s the important thing. To society, since I have a criminal record, I’m labelled a criminal. People are too quick to judge: when you’re using, people call you all kinds of names—slut, cow, junkie, bitch, etc. Now that I’m sober, people see me as a good person who knows what she’s doing, and also, importantly, a responsible citizen. I also belong to L’Addict, an association for current and former drug users.

I’m leaving on December 30, 2018, for a three-month therapy program in Ottawa, and I’m proud of it. This will be my challenge for 2019. I’d like to say that yes, it’s hard, and no, it’s not easy, but take the time, it’s worth it. I’m doing really well and I want things to get even better. After my three months are up, I’d like to get my driving licence back, finish paying off my debts, and be very happy and especially smiling. Don’t be afraid to ask for help—it’s worth it. Good luck, everyone. My name is Mélissa C.

Narrator:

Problematic opioid use is devastating Canadian lives. The numbers are tragic and staggering. These are the stories behind the numbers. This crisis has a face. It is the face of a friend; a co-worker; a family member. Meeting those eyes, and seeing our own reflection is the first step toward ending the stigma that often prevents people who use drugs from receiving help. To learn more about the opioid crisis, visit Canada.ca/Opioids.

This audio series is a production of Health Canada. The opinions expressed and language used by individuals on this program are those of the individuals and not those of Health Canada. Health Canada has not validated the accuracy of any statements made by the individuals on this program. Reproduction of this material, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes is permitted under the standard Terms of Use for Government of Canada digital content.

Donna’s Story

Donna reflects on her relationship with her daughter who struggled with substance use. Let’s listen to Donna’s story…

Donna’s Story

Donna reflects on her relationship with her daughter who struggled with substance use. Let’s listen to Donna’s story…

Darryl’s Story

The question is, how does a doctor and somebody who’s so well educated get an addiction to fentanyl? This is where Darryl’s story begins…

Darryl’s Story

The question is, how does a doctor and somebody who’s so well educated get an addiction to fentanyl? This is where Darryl’s story begins…

Charlotte’s Story

We know that it’s real. Yet, we tell ourselves that it couldn’t happen to the people we know, the people we work with, the people we love. This is where Charlotte’s story begins…

Charlotte’s Story

We know that it’s real. Yet, we tell ourselves that it couldn’t happen to the people we know, the people we work with, the people we love. This is where Charlotte’s story begins…

In Plain Sight is a Health Canada audio series that explores the personal stories of people affected by the opioid crisis.

Every day, approximately 11 people die from opioid overdoses in Canada.

We see this on the news. We know that it’s happening. We know that it’s real. Yet, we tell ourselves that it couldn’t happen to the people we know, the people we work with, the people we love. That it couldn’t happen to us.

The reality is, the opioid crisis is happening right before our eyes, in plain sight, and it can affect anyone. There are thousands of stories waiting to be heard.

This is where Charlotte’s story begins…

Charlotte:

Hi my name is Charlotte Smith. I guess my problems really started when I was about uh – I was almost 13 and my biological mother came to England, because she is British but she had moved to Canada and had gotten married, and uh, she but had never been in my life. I was adopted out when I was six months old.

When I was about 13 she wanted to find me and re-adopt me and take me back into her custody so she did. And she paid for my immigration to Canada. Sponsored me in. And, it was a pretty devastating transition for me. I was very homesick. I was ok for almost year and we were in our honeymoon phase, but after that, everything went downhill.

I started cutting my arm and avoiding my biological mother. I stayed out a lot with friends. I didn’t want to go home. I didn’t feel like I was wanted there.

I had found some recordings that my mother had done of her self-therapy and she was just sobbing into the recording saying how I wasn’t really like her daughter, and how I didn’t speak like her and I didn’t have the same values as her and she was clearly devastated by that.

As my mental health declined, her behaviour towards me also declined. She became very emotionally abusive.

Eventually, she dropped me off outside of a foster home where I had babysat. This was a few weeks before Christmas, when I was 15. I cried for about three days straight. After about a week of being in this foster home, where I wasn’t a ward of CAS (The Children’s Aid Society), but my mother was paying rent to the parents to keep me there, which had been cleared by CAS.

I was so scared of being alone, you know. I didn’t have any family in Canada besides my biological mother and I thought if things don’t work out at this foster home, I’m just going to be completely alone in a country where I really don’t feel I belong.

So their marriage dissolved. The foster home was completely destroyed by that. I ended up living on my own on and off with that man and in and out of horse farms that I had also volunteered at when I was 13 and 14, since coming to Canada.

So horses, and that experience, really provided great opportunity for me for housing – because I had the experience mucking stalls – when I came back to these places I was a 16-year-old homeless girl. They would take me in and let me work there for a room. But I also started using a lot of ecstasy. I had never done any drugs before being kicked out of my house.

But after that, everything just seemed even more hopeless than it was before. It was just a way to cope. It was a way to cope with being homesick from England, and then it was a way to cope with the loss of my newly found biological mother.

Narrator:

So at just 18 years old, Charlotte left Canada and returned to England – with no life skills or experience living on her own.

But the ties she had to Canada began to tighten and she soon found herself leaving England to return to the only life she really knew.

Charlotte:

Then things went further downhill because I had failed at going back to my home. I had come back to Canada and now the farms were out of reach for me.

So I just started doing more drugs. I met some people who were prescribed OxyContin and I started to take that. And, at first I thought this was great, because it allowed me greater strength capacity. I got a job in construction, and I was able to keep up with the men. I was able to lift the drywall sheets – everything – and keep that energy going all day because of these pills. I didn’t realize that I was addicted to them.

They also gave me a lot confidence and I moved in with a woman who was addicted to OxyContin, and her son. And I taught her how to crush them up and snort them because that’s what I had always done with ecstasy. I didn’t realize that that would make her addiction – which I still, I didn’t realize that even she was addicted, but it took her addiction to prescription pills to the next level because she started going through them so fast because the high is more intense but it’s shorter. And of course you build up resistance too. So, then we started having to go through all of her pills and finding ways to buy more. And when I didn’t have them, I would be very sick and the whole world would be gray. Like, apart from the physical sickness.

And the woman I was living with ended up going to detox because of that. And I felt very responsible. She ended up losing her child as well, for a period. But when she came out of detox, she came out with a boyfriend who used crack cocaine and I then fell into smoking crack with her and her boyfriend. And it was fairly easy because it wasn’t my first time seeing crack.

I used to use online dating sites to secure drives places to pick up these ecstasy pills. So I would tell guys that I was going to sleep with them if they would give me a drive so that I could go get my pills. And one time, the gentleman who was driving me around had offered me crack and I spent, I think 4 or 5 days in his apartment, just high out of my mind. Just not fun, paranoid, scared but lighting that pipe and taking the next hit, and the next hit and the next hit. Even though I was shaking and sweating and sketched out.

And I got out of that apartment and I thought, “wow.” And it took me a few days to recover. I thought, “I’m never going to ever do that again and I hope I never see it again,” and I didn’t think I would. But by the time when I saw crack again, when I was 19 now, things had gone so far downhill I really felt like that I had left nothing to lose. I had no family. I had no real future prospects. I had dropped out of high school. There was no hope of returning to my family in England.

I felt like I was a complete failure. So I smoked the crack for the next three years every day. The only times when I didn’t was if I was in jail or when I was working to try to get more drugs – which was through shoplifting or sex work. And of course during this time I also kept doing OxyContin but I also started injecting OxyContin and morphine and cocaine as well, which was a very terrifying experience actually.

Even though I did it, it’s not that it didn’t scare me. I would go into these houses where I would see people searching for veins for hours – just poking needles into their arms, just trying to find that hit. And having abscesses, and having seizures, and just using dirty needles, sharing needles, and as shocking as that was, I honestly just felt as if I was finished – that my life was never gonna be what it could been if perhaps, I hadn’t come to Canada or if my mother hadn’t kicked me out.

So I followed suit, and I and I used dirty needles, and I shared them and I did all of those things. And, uh, really the only reason that I got out of drug use was through pure luck. And that’s what’s so frustrating about the system as it is right now, is that there is no standardized state-sponsored help for people to get out of addiction or homelessness. There is no reliable solution.

Everybody, sort of, is left to find their own way, which I was lucky enough to do. Because one of the last times that I went to jail, I knew that if I got out of jail and I went back, picked up the pipe or the needle, that I was going to end up with AIDS or HIV. A lot of my friends at the time had one of those diseases or the other.

So I called a friend, and he agreed that when I got out of jail, that I could move in with him. So, I went out there and I didn’t come back into the city at all for probably almost a year. And in that time, somebody helped me get a job at a horse farm. And every day that I walked into that farm, I saw the horses and I knew that if I were to pick up a pipe, if I were to go in to Ottawa and to go downtown, I would lose everything. All the trust that I built up with these people and all the privileges I was given to take care of these animals. So I was able to stay clean.

Then I did a year of college. Which now I’m starting my masters in September. I’ve got – had many opportunities to conduct research on populations that I used to be part of – like sex workers, drug addicts and homeless youth.

So, finally I can sort of see a future for myself. And it’s a future where I believe that I’ll, hopefully, be able to help some of those people that I’ve left behind. Cause I definitely do have survivors guilt, PTSD from, uh, the experiences of being homeless and being addicted to hard drugs. So that’s something that I still struggle with. I have a lot of nightmares, where somebody will be overdosing and I can’t save them. And those happen all the time, and that’s something I have to continue to try to put behind me.

I also still struggle with active addiction. So, I’ve been sort of somewhat on the straight and narrow for 5 years. Addiction is very powerful and I seem to not be able to escape it – and I wish that something could take it from my mind. But so far I haven’t found a way to do that. And there are so many memories that I have of using in Ottawa – that wherever I go, it’s just constantly in my face.

And I know that addiction and drug use is invisible to a lot of people that have not experienced it. But when you have experienced it, it’s unavoidable. And wherever you go there’s reminders of it and there are triggers that cause you to have urges to use and they can be very hard to deal with and there’s not necessarily a lot of help for that beyond, you know, weekly meetings with counsellors or group sessions with other former users like, NA (Narcotics Anonymous).

But really it’s something that’s always there inside you. And even I’ve watched my friends die and people are dying every day in Ottawa from opioid use. And as painful as that is for me to see those people dying, it’s still not enough of a deterrent for me to not use when… when that urge strikes me. And that makes me feel disgusted at myself. And I don’t know what the solution is.

Narrator:

Fifteen minutes. That’s all it took for Charlotte to take us on a life journey.

She then shared reflections on her life, how the world came to treat and perceive her – how she began to see herself differently too.

Charlotte:

One thing I noticed when I was using crack and heroin and OxyContin and morphine on the streets, was that you are no longer treated like a young girl. You become seen as responsible for yourself, as an adult who is making – conscious of their decisions – and just simply choosing the wrong path. Which I very much felt like I was not an adult and that I still had the mentality of when I was 15.

So to be treated like an adult was difficult, because when you go, say to your social worker for a welfare cheque and they are very unsympathetic that you’ve been using or that you can’t find a place to live it’s very damaging. And… it’s awful because you so badly want people to see that you are a 19-year-old or 20-year-old girl, and that you need help.

But they tend to view you like just the way they see any other street user and that it’s your fault for the position that you’re in. And it’s very uncomfortable to ask for help because you don’t feel like you deserve it, because you start to think that, “I am the cause of my own demise here and I did do this to myself.” Which is to a point true, but there were also a lot of other complicated issues that played into me taking that choice to use drugs.

And I think that that barrier that comes up between you as a young drug user and the rest of society – it causes you to look for belonging in other ways outside of the mainstream. So you become very close to the older people on the street the older addicts who are around you and you forge some sort of community with them. But it’s certainly not a healthy community and that’s not because of the individuals themselves. They may be very nice people and they’ve also come from so many different backgrounds, but the lifestyle associated with drug use on the street is very toxic.

So I met people who were actively engaged in sex work and who were not honest about that when I first came on the scene. So they would set me up on dates with men who I honestly, naively, stupidly thought were, maybe wanted to date me. And they were not. They were paying the people I knew to have sex with me and I had just had no idea, and that’s what I mean by that I was a child even though people were treating me like I was an adult.

I was very naïve and people wouldn’t believe me when I said I didn’t know they were pimping me out. They would just think that oh you’re a slut. But no, I really didn’t know and I when I did realize, I tried to kill myself.

The girl that I was staying with, who was an IV drug user, she ended up being all I had. I felt safe with her and then when I realized that she was selling me to men and that she really didn’t care or that she did care about me, but her need for drugs was so powerful that she was willing to risk my life or my safety to get those drugs, I was devastated and I stabbed my arm multiple times with a carving knife and she had to call an ambulance. And because of that, she wouldn’t let me go back to her place. Because I was a heat bag then.

Because of me she had to call 9-1-1. Which is a serious offense in this subculture of drug use and homelessness and sex work because police are pretty awful to drug users, in my experience. And it’s very hard, even if you’re watching your friend overdose, you do not want to call 9-1-1, because you don’t want to get in trouble. You also don’t want to call 9-1-1 because you know that the person laying on the ground does not want to wake up and see the police in their face and be taken to jail because of their addiction. And that is a call I have had to make. And I tell you that I did leave my friend on the floor until her lips were blue before I called 9-1-1 because I was scared of the police.

And the time that I tried to kill myself when I was first realizing that I’m in this subculture, where people can only care up until they get their next hit.

When I was released from the hospital in Quebec, I was covered in blood. This is another example of how you’re not treated like a young girl – when they took me in, they were basically laughing at me. They weren’t taking it seriously that I had tried to kill myself and they told me that I just, you know, I was just in drugged-induced psychosis, basically and that I was jonesing and that I just needed another hit, and that’s why I was acting out.

They didn’t give me even any bus fare. They let me – they released me to a place where, you know, outside of the hospital where I had no idea where I was and I had to find my own way back to this girl’s house… not knowing that she would also reject me from there. But just the lack of compassion… I know to them, I was wasting their time because they had real people with, what is considered real health issues – that aren’t addiction – to deal with. But I really did need their help. And if an adult, I feel like would have treated me like I was a young girl who needed help, things could have been different. But they didn’t even try. And that all contributed to me just giving up more and more.

I was worthless. I, uh, walked all through the streets of Ottawa in those bloody clothes and nobody offered me any help. Except a bus driver let me on for free eventually. And the only places that I could go were crack houses… and I call them crack houses but these are houses where there is a lot of prescription drug use its not all crack. It’s all kind of drugs, a lot of opioid use, a lot of needles… and those are the people that ended up taking care of me and letting me sleep on their couches with their bed bugs until I was healed enough to get my stitches out and carry on about my business.

And by then there was no other options outside of sex work because – I was too awful looking to get away with shoplifting. So, when you go into shops when you’re looking clean and tidy, they don’t notice you and you can get away with a lot more than when you walk in in dirty clothes and scabs all over your face and arms. You get noticed very quickly. So sex work becomes one of the only options because men, and not all men, but a lot of men don’t seem to mind if you are dirty and if you have scabs and if you are sick.

Every other part of your identity beyond drugs and prostitute and homeless are erased and that’s what people see. They see an addict and they can justify many actions against you by that. They can justify throwing you in jail, or kicking you out or having sex with you when you clearly are in no shape to be doing that because you’re just an addict – and you’re no longer a young woman who was scared, who needs help, who was a new comer to Canada. You’re just seen as disposable.

I don’t think that people treat young girls who are not homeless addicts the way that they treat homeless young addicted girls and I wish that is something that could be changed. I know a lot of men that have done terrible things to me, have daughters at home that they would kill somebody for doing the same thing to. But because I made the choice to put a needle in my arm I lost all the privileges that many humans in Canada do get. The rights over their own body – to not be touched while they are sleeping.

And just because I made the choice to sell my body or because I made that choice – because it was the only choice that was left to me…doesn’t mean that I can’t be raped. Because I did get raped and there are a lot of other girls who are out there getting raped too. There’s just no respect for addicts.

Narrator:

As far as she has progressed in life, sobriety is still a source of shame for Charlotte and she is always aware what the world expects and what is realistically possible.

Charlotte:

People do tend to think that when you stop being an addict, you’re supposed to at least stop doing all drugs and I think that’s taught in a lot of these recovery practices. But for me, that’s not the case and I think it is a dangerous misconception.

Because if you tell me that I can’t smoke pot or drink alcohol for the rest of my life, I’m going to be very anxious and panicky just the thought of that to not have that kind of safety net of more socially acceptable drugs.

When I first got off the streets, marijuana really helped me stay away from going back to the hard stuff. It also helped me sleep at night. I find that I have less nightmares. I find that I have less reoccurring traumatic thoughts about my past when I’m smoking marijuana. And I’m ashamed of that pot use to a certain extent because… while it is legalized and there is a lot less social stigma around it, I think or I feel like in professional worlds, that it might delegitimize me in the field of research because I use it so often. I feel like people may think that I am not a serious professional or they might worry that I’m conducting research stoned. I don’t use it for the day to day activities. I use it as a crutch at night.

What I hope to do is transform the research process into one that can be actually part of prevention and intervention for youth homelessness and addiction. So by helping to facilitate positive, meaningful youth engagement with youth who are at risk of homelessness and addiction, or who are experiencing those things. And trying to send the message that when we’re in places of privilege, like I am now, like, each interaction that I have with a youth who is experiencing hard times, can be a positive one.

It can be more than just a simple interview where I’m siphoning knowledge from them about their experience, to publish towards my own career. I can try to offer them resources, I can try to offer them hope, and at the very least, I can ensure that I’m giving them cash dollars for their participation in my studies, rather than gift cards, which are not a form of harm reduction, the way that I see cash is.

Because if I’m giving cash to my participants, then and they need drugs, then it’s my line of thinking that they’ll have to do one less awful thing to get those drugs because they have that $20. And I think that there is a perception, that when you’re giving addicts money, you’re enabling them. I think you need to respect people’s wishes too. If somebody is asking you for money, it’s because they need money. And it’s not up to you what they do with that money. And I think that you can provide some semblance of safety by giving them that money, rather than a gift card – which will not help them get the drugs they need… in which will mean that they will still have to go walking down the streets trying to catch the eyes of drivers who will stop and ask them if they want a date.

I hope that in all the research that I do I can engage meaningfully with youth, I can get them excited about the possibility of returning to school or following dreams outside of school that are off of the streets and away from drugs.

And I think from the youth that I have worked with so far, they do appreciate that I come from a background similar to their own and they do seem to be more willing to talk to me about more intimate details of their experience because of that. And they’ve told me that. And they seem also to be excited that I’m doing so well, and I think it gives them a sense of hope that, well maybe, you know, the future doesn’t have to look homeless and addicted. Narrator:

Problematic opioid use is devastating Canadian lives. The numbers are tragic and staggering. These are the stories behind the numbers. This crisis has a face. It is the face of a friend; a co-worker; a family member. Meeting those eyes, and seeing our own reflection is the first step toward ending the stigma that often prevents people who use drugs from receiving help. To learn more about the opioid crisis, visit Canada.ca/Opioids.

This audio series is a production of Health Canada. The opinions expressed by individuals on this program are those of the individuals and not those of Health Canada. Health Canada has not validated the accuracy of any statements made by the individuals on this program. Reproduction of this material, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes is permitted under the standard Terms of Use for Government of Canada digital content.

Amy’s Story

Josh had a great sense of humour and loved playing sports. He went to a party one night and everything changed. His sister, Amy, shares his story…

Amy’s Story

Josh had a great sense of humour and loved playing sports. He went to a party one night and everything changed. His sister, Amy, shares his story…

In Plain Sight is a Health Canada audio series that explores the personal stories of people affected by the opioid crisis.

The most recent data shows that every day approximately 12 people die from opioid overdoses in Canada.

We see this on the news. We know that it’s happening. We know that it’s real. Yet, we tell ourselves that it couldn’t happen to the people we know, the people we work with, the people we love. That it couldn’t happen to us.

The reality is, the opioid crisis is happening right before our eyes, in plain sight, and it can affect anyone. There are thousands of stories waiting to be heard.

Josh had a great sense of humour and loved playing sports. He went to a party one night and everything changed. His sister, Amy, shares his story…

Amy:

We grew up in a small town in Nova Scotia. I’m one of four siblings. I’m the oldest. Josh is, the middle child. We had a very good childhood – very typical, middle class. We all were involved in different sports and had our own interests. I was in gymnastics and volleyball, Joshua loved hockey, skateboarding and snowboarding, played sports throughout school. We were all very close.

Josh always was a risk-taker. And he had a fabulous sense of humour. He was always the class clown and the person that could make people laugh. He also enjoyed volunteering at my grandmother’s daycare. He would spend summers there helping her out, and taking part in activities, with the other kids. He really enjoyed, connecting with younger people, too, as he got older. And kids loved him because he did have such a great sense of humour and was very playful and even into his twenties was always the kid at heart.

When he left school, he went out to Alberta. He was working out west as an arbourist. He loved doing that. That was something that, he felt a sense of accomplishment in… getting the training and getting promoted. And that’s kind of when our lives changed, forever.

At first it was great news. We had heard Josh had got a promotion in Nova Scotia to move back, home where all our family is and we were all thrilled. And he was pretty proud of himself, too, because he had the ability to hire some of his friends when he came back to Nova Scotia from Alberta. And he thought that was pretty cool. He was 21 and just a zest for life, starting out on this new adventure. Purchased a new car coming home, I can remember he was so proud of it, always shining it up. Looking for a new apartment. Just a lot of things to look forward to.

And on March 19th he’d been home maybe two months, maybe not even that long. I’m not quite sure, but it was still relatively new. He was staying with someone and getting all these things in place, like apartments, buying furniture, things like this.

It was a Friday night. He had finished work that day. He was supposed to, meet me at a cottage, a family cottage, which was about an hour away from where we lived. And he called and said, “I’m just so tired, Amy, I’m sorry. Work was really long today. I need to pick out this furniture to be sent to the new apartment and I’m just too wiped to drive out there. There’s always next time.” And those were actually the last words I ever heard from my brother, is “there’s always next time” which is so ironic, because unfortunately there wasn’t.

We had just a regular night at the cottage. I had no sense that anything was not the norm. I woke up that morning, packed up our stuff, headed back to our hometown. I took my daughter swimming. We were in the pool, having fun. Again, no sense that anything’s wrong. When I arrived home, I was getting her changed out of her bathing suit and my phone just was ringing incessantly. And I could start hearing notifications go off. And I was actually getting quite irritated — I’m trying to get a wet bathing suit off a toddler and I’m thinking, “what is so important?” like, you know, who is this?

So, I root through my swim bag, get out my phone, answer the call and it’s my younger sister. And just the tone in her voice, I knew something was… was terribly wrong. She asked me if I was alone. I said, well, I have Chloe with me, my daughter. And she said, “is anyone else there with you?” and I’m like, thinking why, why does that matter? And she said something happened. I said, “Just tell me, just tell me, Mallory.” And that’s when I found out.

She said, “Josh went to sleep last night, and he never woke up.” And just a wave of shock and… I can’t even explain. I’ve never had those emotions before in my life until that day. And not knowing what could cause something like this to happen. My brother was an extremely healthy, happy, 21-year-old man. I just couldn’t understand. How does he go to sleep and not wake up?

He had had spleen issues the year prior, so we immediately thought, well maybe his spleen ruptured in his sleep and nobody, you know, nobody was with him. We waited for the medical examiner a few days later to give us a call and that’s when we realized that Josh was perfectly healthy. His cause of death had nothing to do with anything physical. And that’s when she asked us if substances might have been involved.

We were kind of taken aback by this. We were expecting answers that day, not more questions and then she said we’d have to wait for a toxicology report. So that’s when my family started to call people who he was with that night, friends, trying to find out what he was up to, and if drugs could have been involved.

And then quickly we found out that he had attended a party with a group of friends. It was a birthday celebration. And the prescription painkiller hydromorphone was being experimented with and offered to people and he, he tried it and that ended up being the cause of death, we found out later in the toxicology. We had to wait a long time for those answers, but we found through friends and we pretty much knew, after speaking to people that that was very likely the cause. And it was absolutely shocking.

I had no idea that experimenting with a prescription painkiller, which is prescribed by a doctor could have such permanent, irreversible damage. I always thought that people who were harmed by substance use developed addictions, and there was this long period of time where they would struggle, and family could reach out and help them and get them into treatment.

I never dreamed that one night I’d be talking to my brother, everything’s happy, all is great in the world, and the next morning I wake up and he’s gone. Because of one, one pill. It definitely evoked feelings of helplessness because, looking back, I don’t really know what we could have done except, now — this happened in 2011 — so in 2011 there was no naloxone available without prescription. There was very little awareness about opioids. There was no Good Samaritan Law. So these are the types of things that I think could have impacted that situation that weren’t accessible to people and people weren’t aware of seven years ago.

Narrator:

Devastated by her brother’s tragic and unexpected death, Amy found herself stepping into an advocacy role in the hopes of broadening awareness of how the opioid crisis could affect any one of us.

Amy:

It was nine days after Joshua passed when I started my advocacy. I didn’t really plan on starting advocacy, I just knew that if this could happen to my family and my brother and I had no anticipation that this was even a possibility, that there was a lot of other people in the world in the same position and they needed to be made aware. And we needed to act on this issue. Because my family was not aware until my brother passed away and all I want to do is prevent other people from learning about the crisis in that way — through prevention, education. There’s lots of things we can be doing to prevent these tragedies, because they are preventable deaths.

There is no magic bullet, but first of all we need to reduce demand. We need to save the lives of those who are currently at risk and using, through safe consumption sites, accessible naloxone, accessible medication-assisted treatment. We need to treat the people that are currently using and save their lives, and while doing that we can be preventing unnecessary exposure to opioids through more cautious prescribing, education, awareness. We need to be working on both sides of the crisis to make a meaningful impact and save as many lives as possible.

Because, I don’t know how many times I’ve heard the narrative of as well – I know illicit fentanyl is ravaging our country right now. But I don’t know how many stories I’ve heard where people were first exposed to opioids through prescription, thinking they’re safer, they’re cleaner — which they are, in a sense, they’re definitely safer than illicit fentanyl — but, a lot of people are initially exposed in that way and then once they develop tolerance or a substance use disorder, it can often then lead to seeking stronger alternatives, cheaper alternatives, if prescription pharmaceuticals aren’t readily available or, or not strong enough.

So, we need to be working on both sides. We can’t arrest our way out of this issue, too. I think decriminalization of personal use would be very helpful. It would help people engage in treatment. Because when you criminalize people who use drugs, then they do it… they hide it. They do it in silence.

Because lots of people, even like my brother, maybe if he lived that night and continued using opioids and developed a substance use disorder and needed to seek help, when you criminalize drug use, you know with his job, with his everything else, that you have so much to lose because you’re admitting to breaking the law by saying that you use drugs. So, I think it would be very helpful for people, if they could seek out help without the fear of being criminalized. Those are some things I think that would be very useful.

The criminalization too is so related to stigma. I never experienced stigma in my life until my brother passed away from a drug-related death. I never knew what that felt like, but I quickly learned.

When I began my advocacy and started to speak out publicly, I had to learn very quickly not to read the comment section because the hatred towards people who use drugs, in society, and the misunderstanding that these people are “less-than” is very hurtful and it’s very prevalent. I think that’s one of our biggest barriers to implementing some of these interventions, is the idea that substance use is a moral issue, not a health issue. And until we can change society’s thinking in that regard it’s going to be very hard to implement some of these interventions or get support, get political will, get public support for these interventions. And I think that that’s also what’s allowed this crisis to perpetuate.

Seven years ago, when my brother passed away –most, opioid-related deaths were prescription-related. And those numbers were still very high, like hundreds of people in Alberta dying per year. Numbers have stayed constant in Nova Scotia. Even in Ontario, hundreds of people a year dying from opioid-related deaths as far back as seven years ago. And, but nobody knew it was really going on and nobody really seemed to care. And I think that had a lot to do with stigma. These are people that, you know, are doing it to themselves. This is not really an issue that helps people in politics or, you know, people that have special interests to pursue. But now that we created such a large opioid-dependent population, organized crime has entered and they’re willing to feed that with illicit fentanyl which is just devastating.

It really didn’t need to get to this point, but the stigma around the issue allowed it to kind of, grow in silence and it perpetuated it without people being even aware that this was happening until it got to such, large, devastating proportions.

I think it’s helpful for people to share their stories and bring a face to the issue. And sadly, I always say this is a club you don’t want to join, but so many people have, unfortunately. And, I see much more awareness now of people sharing their stories than seven years ago when my brother passed. And I do think that that is very helpful to actually see the faces of the people, hear from the families that are being affected, the family voice and, even the people that are currently using, people who use drugs, they have a voice. And their voices matter. So, people with lived experience have an important part, to play in this issue and they need a seat at the table. In hearing our voices, in seeing our faces, will hopefully reduce stigma.

Narrator:

Problematic opioid use is devastating Canadian lives. The numbers are tragic and staggering. These are the stories behind the numbers. This crisis has a face. It is the face of a friend; a co-worker; a family member. Meeting those eyes, and seeing our own reflection is the first step toward ending the stigma that often prevents people who use drugs from receiving help. To learn more about the opioid crisis, visit Canada.ca/Opioids.

This audio series is a production of Health Canada. The opinions expressed and language used by individuals on this program are those of the individuals and not those of Health Canada. Health Canada has not validated the accuracy of any statements made by the individuals on this program. Reproduction of this material, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes is permitted under the standard Terms of Use for Government of Canada digital content.

Stigma stops people from getting help

For Lori – a doctor – substance use-related stigma prevents her patients from seeking treatment and delays their recovery.

Stigma stops people from getting help

For Lori – a doctor – substance use-related stigma prevents her patients from seeking treatment and delays their recovery.

My name is Lori Regenstreif, I live and work in Hamilton and I’m a doctor and an addiction medical specialist.

To come out and say that I have this story of this one time where I witnessed stigma experienced by one of my patients or I saw it happening myself is really challenging because for most of my patients it’s normal to experience stigma.

Where is the stigma coming from? Some of the drivers I think are really systemic structural and historical. I think it also comes from fear. People are afraid that, that’s a human just like me, could I be like that or I have a relative who has that problem, could they end up like that, that person is scary. The other thing is fear of the person when most of the time people are harmless.

There are people out there with severe alcohol or opioid abuse disorders who are working, who have families, they have children, they come home, they drive, they do all of those things, they pay their bills most of the time, they may have money problems, but they keep it under wraps, for whatever reasons they’ve got some protective factors that keep them from being visible. There’s a huge huge population in our society like that. They come to me eventually but it takes them awhile because of the stigma and because they don’t identify with the people in the street that we see. Meanwhile on the other end of the spectrum are people who have come to total desperation, they’ve lost everything, they may have not had everything in the first place and now they’ve lost whatever they did have, in terms of money, relationships, social supports, housing and of course we’re going to see them.

Substance use related stigma affects my clients in their ordinary lives and in their recovery because I absolutely believe that it sets them back and prevents them from being able to recover because it adds barriers to their attempts to get better… People will avoid coming to the hospital or doctor when they’re very very sick or they’ll avoid coming to see a nurse or somebody because they are ashamed of what they’ve done and they’re afraid of being told, “well you shouldn’t be doing that, why don’t you stop doing that?” and that’s classically people don’t understand, they don’t have any education perhaps or they don’t have training with working with substance use disorder… so their approach is very hurtful.

We have to educate ourselves, we have to educate each other, our children, our co-workers, our learners if we’re in a teaching position because it’s really the people around us and the people we look after that’s our society and if we can do all that I think we can really start to feel a shift.

The words you use could save a life

Gord Garner, Chelsey June, and Jaaji of Twin Flames chat about using positive language when discussing recovery from addiction.

The words you use could save a life

Gord Garner, Chelsey June, and Jaaji of Twin Flames chat about using positive language when discussing recovery from addiction.